I have an earworm these days. It’s from The King and I, and it Will. Not. Stop.

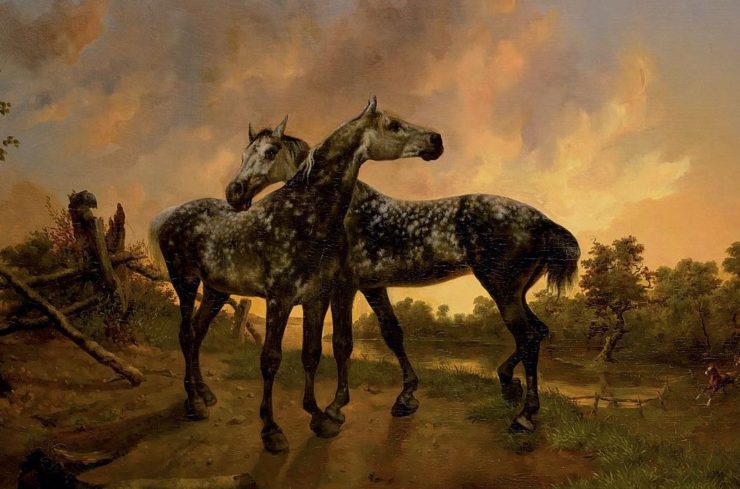

Because, you see, I have adopted not one but two animals from rescues of repute. First, in July, a kitten. Then, in August, a horse.

Both have come into existing herds, or in the case of cats, I believe the collective noun is a clowder. I still call it the cat herd, but that’s me. One has been integrated into the full herd. The other hasn’t, for sufficient and proper reasons. But he’s still very much a part of the assemblage.

It’s been interesting to be in the zone for both a cat and a horse at the same time. Filling out rescue applications. Lining up the references. Keeping contact with the rescue. Arranging meetings and vets and deliveries.

Both animals come from loving homes and good care—the kitten from an experienced foster, the horse from a farm that was shutting down and needed to place a very special individual in a particular kind of home. That’s a blessing for them, and for me, too. They’re well socialized, healthy, well fed and treated. As a bonus, I got to meet the kitten soon after he was taken in by the rescue, so have known him since he was a little over three weeks old. The horse was pretty much a complete stranger, but I know his breeder well, I know his family, I have one of his sisters and have had or worked with a number of his other relatives. I even met him when he was a yearling, though was brief and I was more focused on the filly I would be bringing home when she was weaned.

All of these prerequisites were nice and pleasant and helpful, but when the carrier came through the door and the horse van arrived at the end of the driveway, it was still a brand new world for both the animals and me. They didn’t know about all I had done to get ready. Nor did the respective herds at home know what I bringing in.

That moment, when you introduce the new member of the herd, is always a gamble. Will the other herd members accept him? Will he accept them? Will it be a quick and easy process, or will it take a while? Maybe even forever, if one or more of the animals in the mix takes a lasting dislike to the newcomer?

In the case of the kitten, I had a process in place already, having adopted a pair last year. One of the pair developed a rapid and terminal cancer in the spring, and his bonded sister was miserable without him. She tolerates the two older cats, and they more or less tolerate her, but she needed a brother. A playmate, a kitty-pile companion. Someone near her own age, who could fill the hole her late sibling left behind.

So we did the more or less standard thing. Kitten in his own room for a few days, gradual introductions to the larger house and to the other cats one by one. There’s always a chance that it won’t work out, which would mean separate accommodations for the various configurations of cats (and one dog). I could do that if I had to, though it wouldn’t have been the result I hoped for.

Fortunately, the introduction did eventually succeed. The cat who needed a brother was the last to accept the interloper, and there were some dramatic moments along the way. But one day she stopped trying to kill him. She deliberately went and lay down beside him where he was curled up on my feet, looked me in the eye and said, This will do. And they’ve been best buds ever since.

Buy the Book

A Marvellous Light

Although there are significant differences in personality, needs, and psychology between horses and cats (and dogs, since there’s one of those in the mix as well), introductions are a similar enough proposition that if a person is writing about horses, they can to a large extent extrapolate from their experience of cats or dogs. You start in a separate space, get them used to each other’s presence, then when things have settled down to the new routine, you can start bringing the newcomer into the herd. First with an individual you think may be compatible, then if that works out (no huge fights, no injuries or worse), bring the others in one by one and let the new configuration settle itself out.

It helps if the first horse introduced is one of the leaders of the herd. That horse’s favor will make it easier for the rest to accept the newcomer, and may protect the new arrival from the others. If the leader does not accept the newcomer, it’s much harder to integrate them; it may even be impossible, and the herd may have to be divided, or the newcomer may end up in a separate space. I’ve had some horses never be accepted at all, and I’ve had some in a separate turnout with one or two other, compatible horses. It’s very much a case of “It Depends.”

Just as cats and dogs will attack an interloper and try to drive them out, horses may do the same thing. Mares will get into epic kicking battles, or they will chase and viciously bite each other. Geldings may do that or they may channel their stallion roots and go head-on with rearing and biting.

What we want to see when we’re making introductions is a lot less violence. There may be posturing and threatening, and some biting and kicking at each other. That’s how horses determine who gets to lead and who gets to follow. The key element is whether both sides make their statements and then settle down. With luck, one or both parties will make faces, brandish a hind foot, or paw the ground, but then when the other whirls into action, will lower their head and back down. And the aggressor will cease and desist, and a few minutes they’ll be grazing amicably.

This may go on for a while. Hours or days. They’ll discuss protocol, establish precedence, and if there are multiple horses involved, determine where the newcomer fits into the established order. That order may change, with individuals settling into different configurations, and friends and favorites rearranging themselves. There may be smaller flurries as that happens, until the herd finds a new equilibrium.

In general it helps if the herd is either all mares or all geldings. Mixed herds can work, but multiples of one gender may get competitive. Again, as I said above: It Depends.

The big honking exception to all of this is a stallion. Herds of stallions can and do run together. In the wild, they’re called bachelor bands. In the domesticated world, at large breeding farms and state studs, the colts and younger stallions may share a pasture.

Generally however, when the ungelded horse matures around age three or four, he tends to be separated into his own space. That’s when the hormones really start to come in, and that’s when the boys are wired to go out and find or steal their own mares. They will fight, and what used to be play may transform into grim earnest. Even when there are no mares around and the stallions live together in harmony, they still have their own stalls and their own paddocks. They might get along if they were pastured together, but the risk of injury is high. Better and safer for these valuable animals to keep them alongside each other and in each other’s company, but in their own personal space.

So of course, when the I applied to the rescue, the rescue answered, “We have a stallion. Are you interested?”

I was able to answer in the affirmative, because I have accommodations for the wild card in the horse deck. I can keep him separated from the mares but in sight of them so that he feels he’s part of the herd, and I have fences that are strong enough and tall enough to contain him (many jurisdictions in the US have laws regarding the height and composition of stallion fencing). And I’m willing to deal with the differences in behavior between the stallion and the mare or gelding.

So, on the one hand, I do not have to worry about integrating him with the mares and their tutelary gelding. On the other, there’s a whole different set of factors to consider. Not just keeping him in his own space (which stallions generally are OK with, they like to be emperor of their own universe), but managing the behaviors: the pacing, the calling, the letting it all hang out, and I don’t just mean the boy, I mean the ladies, too. There’s a lot of drama, and a lot of distraction, on both sides.

And there as with the cats and the non-stallion horses, it’s always a gamble. Will this individual fit into the established mix? Will it happen quickly or will it take time? Will I get along with him? Will he get along with me? Will he be happy here, and will it all work out?

Or to put it in the words of the song, will we be each other’s cup of tea?

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans (now plus one), a clowder of cats (also plus one), and a blue-eyed dog.